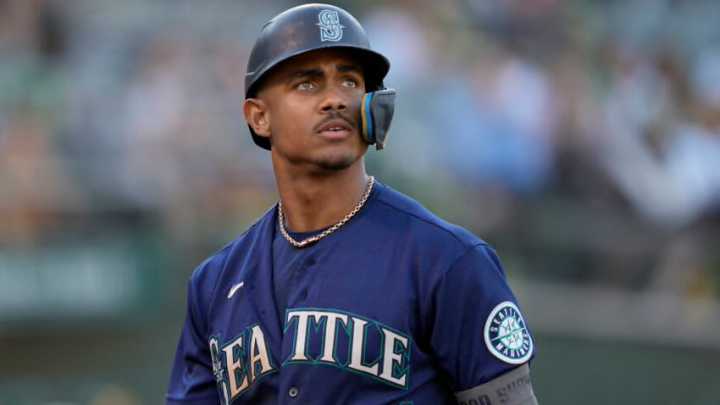

With the Seattle Mariners being the most recent team to sign a budding young superstar to a mega-deal that will keep rookie-of-the-year favorite Julio Rodriguez a Mariner for the rest of the 2020s and into the 2030s, Houston Astros fans may be wondering why they haven’t shelled out that type of deal for the Kyle Tuckers and Jeremy Penas of the world.

The Houston Astros’ stance on not believing in 10-year contracts is the correct front office approach.

The Houston Astros made it clear to Carlos Correa the previous offseason that they do not believe in long contracts. They offered him a five-year contract worth $160 million for an average annual salary of $32 million. That would have been the seventh-highest annual average of any player in the major leagues.

Correa wanted the extra years to go along with it. The Astros said no. They have not wavered on that position with any player. Alex Bregman and Lance McCullers Jr. are on five-year deals while Yordan Alvarez is under contract for six. While it’s harder to retain and acquire free agents if you don’t give them the long-term deals they seek, it’s the correct position if you want to remain competitive over the long haul.

It’s not hard to find examples of why these decade-long contracts for players with loads of potential but little major league experience can be risky prospects.

One need look no further than the season the San Diego Padres are having to see why tying up so much money in one player for so long may not be a wise decision. Fernando Tatis Jr. is signed to a 14-year/$340 million contract. He missed the first half of this season due to injury and will now miss the rest of it due to a performance-enhancing drug violation. The Padres paid Tatis Jr. $24 million this year to play zero games.

Of course, he is absurdly talented and can easily have a bounce-back year next season. But the same could have been said for Astros prospect Forrest Whitley after his 50-game PED suspension in 2018, which was followed by an injury in 2019. This is the risk teams are willing to take to lock up young talent for what could be a bargain price over a decade.

The progression of these mega contracts has not changed in terms of years or money, but rather when in a player’s career the signing takes place. The way it used to be, teams would sign players to 10-year contracts in their late 20s or early 30s after they hit free agency, such as the Alex Rodriguez, Miguel Cabrera, and Albert Pujols deals.

Now after seeing how much production declines as players enter their mid to late 30s, teams are trying to get players locked in during their most productive years in their mid to late 20s. This way, if they produce up to their potential, it would be cheaper than trying to sign them when they would have hit the free agent market in their late 20s or early 30s.

However, between Tatis Jr. missing this entire season as well as Wander Franco of the Tampa Bay Rays missing the first half of the season due to injury after signing his 11-year $182 million contract, it only reinforces the Astros are doing the right thing by not guaranteeing a decade to a player who could become your team’s Bobby Bonilla.

As well, the Mets have a perfect example of their own outside of Bonilla with Francisco Lindor at shortstop. When Lindor was 25 years old in 2019, he had just finished a three-year stretch where he was hitting around .280 every season and averaging 33 home runs and 88 RBI from 2017 to 2019. That was enough for Mets owner Steve Cohen to give him a 10-year $341 million contract and so far, while Lindor has hit well this year, it has certainly not been a successful investment based on the return they’ve gotten.

Lindor has hit a total of 41 home runs for the Mets in 251 games when he was averaging 33 per 150 with Cleveland from 2017-2019. There’s still plenty of time left in this contract. But is that a good thing, especially if Lindor ends up being a .260 hitter who hits 20 to 25 home runs a year? Not to mention, last year and this year have been his worst in terms of defensive runs saved. He only had three last season and zero so far this year. That is not the $34-million-a-year production the Mets thought they were getting.

Julio Rodriguez is now a Seattle Mariner through the year 2034 and getting paid $17 million a season, the newest of these high-risk, high-reward contracts that have been supplanting the formerly disastrous 10-year deals of the 2000s.

This may be frustrating for Astros fans, who will most likely see a lot of players they love go on to other teams if the front office continues to maintain this philosophy regarding these mega-deals. But, if they want the team to remain in contention consistently, long-term contracts that are difficult to shed can hamper a team’s ability to do that.

Based on the Astros’ history of player development, not to mention the not-so-great history of these super deals, the Astros’ five-to-six-year contract philosophy is the correct one.